On balance, it was a good year. Here's what I got right and wrong:

Right: I was generally optimistic. I thought the economy would continue to grow at a sub-par pace but would beat expectations, which at the time were gloomy. I thought the failure of Big Government (e.g., Obamacare) would show up in the November elections as a mandate for less government and that this, in turn, would bolster confidence in the future, and I believe that has been the case. Real GDP growth for the year will likely be just shy of 3%, and that's meaningfully better than the 2.3% rate of growth we saw in the first four years of the current expansion. However, it still leaves the economy over 10% below were it would have been if this had been a normal recovery.

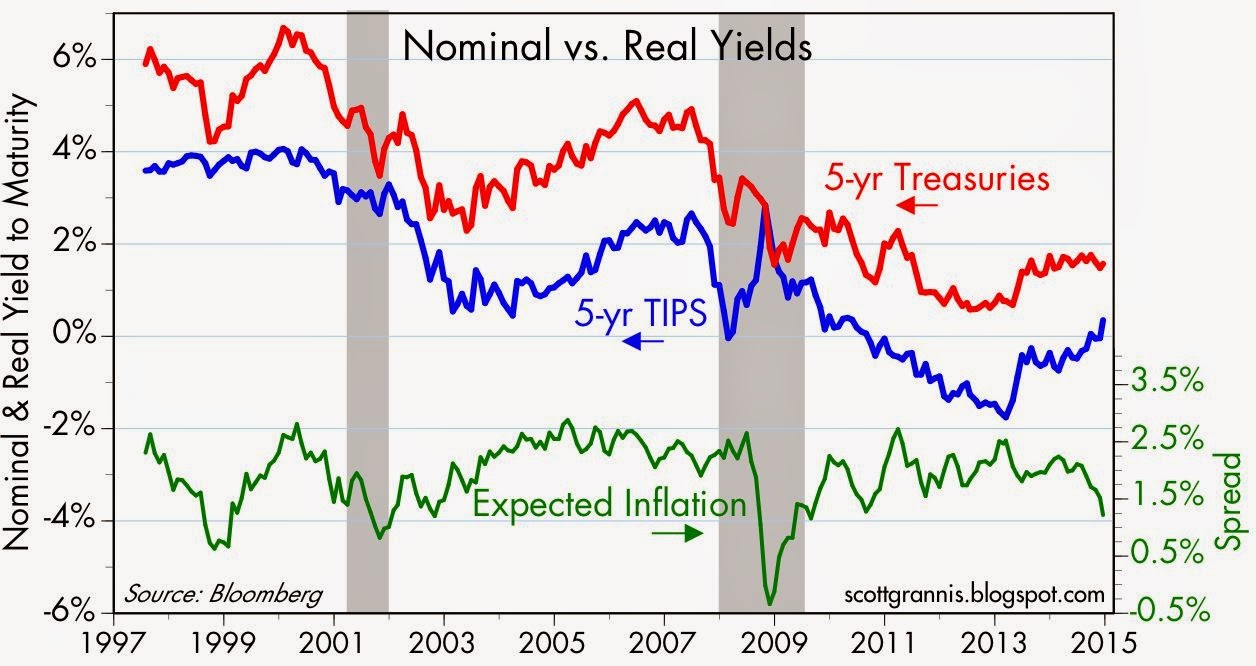

Wrongish: I thought that better-than-expected performance by the economy would result in higher interest rates. Nominal 10-yr Treasury yields fell significantly over the course of the year, but real interest rates (particularly real yields on 5-yr TIPS) increased significantly. This disparity (some real yields up a lot, most nominal yields down) reflects reduced inflation expectations (thanks to collapsing oil prices) and a stronger growth outlook, as I noted earlier this month. So I was half right and half wrong on this call. The rise in real yields is an important development that, arguably, is widely under-appreciated.

Wrong: Once again I was wrong on inflation, thinking that it would rise moderately. While headline CPI inflation did rise in the first half of the year, it subsequently fell, largely due to collapsing oil and gasoline prices, ending the year about unchanged at 1.3%. Core inflation was also unchanged, ending the year at about 1.7%. That's a happy error, since low inflation is better than higher inflation.

Right: I thought the failure of Obamacare (i.e., Big Government) would lead to important changes in the November election in favor of smaller government. Obama's big-government agenda was clearly repudiated, even if Obamacare wasn't overturned. Meanwhile, Obamacare faces steep hurdles in the Supreme Court next year, and a Republican-controlled Congress is likely to succeed in dismantling or improving the program significantly. In any event, I think the political tides have turned enough in market- and business-friendly direction to bolster confidence in the future.

Right: The Fed finished tapering QE3 by the end of the year, as I expected.

Wrong: But the Fed didn't raise rates sooner than expected, as I had thought they would have, given the improvement in the economy. Sharply lower energy prices and low recorded inflation validate the Fed's decision, so it's another happy error on my part.

Right: Cash was unattractive relative to almost every other investment alternative.

Right: Equities would continue to rise even as profits growth slowed because PE ratios would rise, and they did. According to Bloomberg, the PE ratio of the S&P 500 rose from 17.2 to 18.4 over the course of the year, and profits rose 4.3%, down from a 6.1% increase in 2013.

Wrongish: I thought investment grade corporate bonds were unattractive compared to high-yield bonds, but instead they had a positive total return of over 7% for the year, outperforming high-yield bonds that returned less than 3%. Both, however, beat the return on cash.

Right: I thought real estate was very attractive, and REITS were one of the strongest performers of the year. The total return on VNQ was over 30% for the year, vs. 13.7% for the S&P 500.

Right: I thought gold and commodities were unattractive investments. Gold was flat for the year, while industrial commodities fell some 7% and food prices were up only slightly. Oil prices collapsed by almost 50%.

Right: I expected the dollar to rise against most currencies, and indeed it did, gaining over 12%, mostly in the second half of the year as oil prices collapsed and real yields rose. The dollar benefited mainly because the U.S. economy beat expectations and did better than most other developed economies.

Here's what I see in my crystal ball for 2015:

From a big-picture perspective, I think we're somewhere past the middle of a recovery that is going to continue to be relatively sluggish compared to past recoveries for the next year or two. The economy still faces significant headwinds (e.g., very high regulatory and tax burdens), but tailwinds are beginning to develop as government spending relative to GDP has fallen significantly (thus reducing future expected tax burdens) and oil prices have collapsed (thus reducing the cost of doing just about anything). The mandate of the November elections is likely to translate into more market-oriented and investment-friendly policies coming out of Washington in the years to come, and this expectation is already boosting confidence. The economy is not likely to strengthen significantly this coming year, but should do better than it has for the past several years.

I've worried for years that the Fed would be slow to react to a strengthening economy, and that this would fuel inflation. Turns out they've done a better job than most of us inflation hawks thought. I'm not ready to let down my guard, however, so I continue to worry that the Fed will fall behind the curve and allow inflation pressures to build. The rules of the game have changed meaningfully in the past several months, as oil prices have fallen precipitously and the November elections revealed deep-seated concerns among the electorate about an overbearing government and suffocating regulations and tax burdens. Both developments could end up giving us more growth and more optimism as time passes. Oil was very expensive six months ago, and now—in inflation-adjusted terms—it is very close to its long-term average price (see chart below). This is likely to liberate a lot of economic activity around the globe, bringing with it more confidence in the future.

However, as I argued last March, "the return of confidence is the Fed's worst nightmare," since it would reduce the demand for money at a time when the Fed is still supplying plenty of it. Whether the Fed can respond in timely fashion to an unexpected decline in the demand for money remains the most important unknown variables for investors.

However, as I argued last March, "the return of confidence is the Fed's worst nightmare," since it would reduce the demand for money at a time when the Fed is still supplying plenty of it. Whether the Fed can respond in timely fashion to an unexpected decline in the demand for money remains the most important unknown variables for investors.

For the seventh year in a row, I think cash will prove to be an unattractive investment. The yield on cash is still very poor compared to the yields and prospective returns on most other investments. It would likely take a recession to make holding cash worthwhile. Barring a recession, which appears quite unlikely (swap spreads are very low, the yield curve is still positively sloped, real short-term rates are very low, and energy is much less expensive), the public's desire to hold cash will continue to erode, and that in turn will result in lower yields (and higher prices) on equities, real estate, and corporate bonds.

Real estate remains attractive, since it will benefit from a growing economy and it is an decent hedge against higher-than-expected inflation.

Even though profits growth is likely to continue to slow, there is still plenty of upside potential in equities via a continued expansion of multiples, which are only modestly above their long-term average (i.e, 18.4 vs. 16). Multiples are likely to be pushed higher in the absence of a recession and with help from very low interest rates, not to mention the likelihood of an improving growth outlook. The U.S. economy has plenty of idle capacity, idle labor, and capital that can be unleashed with the right combination of fiscal and monetary policies.

Investment grade corporate bonds are relatively unattractive given recent spread compression, but high-yield and emerging market bonds offer spreads that should compensate for higher market yields.

Gold continues to be an unattractive investment, since I believe it is still priced to a lot more inflation and economic weakness than we are likely to see. Commodities are likely to benefit somewhat from an improving outlook for the global economy—which is currently quite gloomy—but still do not offer a compelling investment opportunity at this juncture.

The dollar is likely to strengthen somewhat further, since it is still below its long-term average, and the U.S. economy is likely to once again exceed expectations and outperform most other developed economies. An earlier-than-expected shift by the Fed to begin raising short-term interest rates could also help boost the dollar.

I'm still optimistic, especially since I still see many signs of investor angst: e.g., an elevated Vix index, super-low Treasury and cash yields, and PE ratios that are only moderately above average at a time when corporate profits are setting records. Moreover, I see widespread fears that this year's drop in oil prices could trigger defaults and a wave of cutbacks in the oil industry that could have negative ripple effects throughout the economy. Given that the increase in oil supplies has swamped any reductions in demand (see "Cheaper oil is great news" and "Commodity prices are down, but they aren't cheap"), I think that a new bounty of cheaper oil should unleash lots of activities that were formerly uneconomical. And of course, there's all the hand-wringing over the possibility that the world's major economies might get sucked into a Japanese-style deflationary quicksand. The danger of deflation is exaggerated, and John Cochrane explained why in this post.

If there's any theme from recent years that is likely to repeat in the coming year, it is that equities will continue to climb walls of worry, as illustrated in the chart below: